To pay for his professional flight degree at Purdue University in Indiana, Andrew Hoyler had two choices. He could rely on loans and scholarships. Or he could cover some of the cost with an “income-share agreement” (ISA), a contract with Purdue to pay it a percentage of his earnings for a fixed period after graduation.

Salaries for new pilots are low. Mr Hoyler made $1,900 per month in his first year of work. Without the ISA, monthly loan payments would have been more than $1,300. Instead, for the next eight-and-a-half years he will pay 7.83% of his income. He thinks that, as his pay accelerates, he will end up paying $300-400 more each month than with a loan. But low early payments, and the certainty that they would stay low if his earnings did, made an ISA the better option, he says. “I’ve been able to pay what I could afford.”

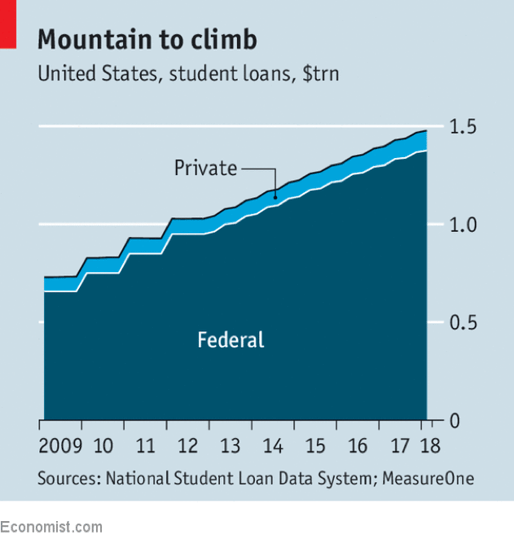

Most American students take out low-interest, federally backed loans, the stock of which has grown steeply in recent years (see chart). Balances are usually written off after 20 years. That is the only insurance built into most students’ debt. Though repayments can be linked to future income, only 29% of borrowers opt for this. And total loans are generally capped at $31,000. In 2016-17, 6% of undergraduates topped up with private loans, which have higher interest rates and no debt forgiveness.

ISAs, by contrast, act as equity, not debt, with investors taking a share in a future income stream. Risk is shifted from students to investors, who can pool and diversify it. Graduates who fail to land steady or lucrative work will pay less than the cost of their tuition. Caps on repayment mean high-fliers do not end up paying back fortunes. ISAs also align the interests of borrower and lender, since investor returns are tied to a student’s career progress. Investors will offer better terms to students at universities whose graduates earn well.

ISAs have been mooted before as a way to spare American graduates from mountains of debt. In 2014 bills were introduced in Congress that would have put them on a firm legal footing—setting maximum loan terms, for example, and ruling that, like ordinary student debt, they would not be dischargeable by declaring bankruptcy. One firm, Upstart, briefly marketed them directly to consumers. But the bills went nowhere and the idea fizzled.

Similar proposals are once more being considered in Congress, but that is not the main reason why ISAs are attracting attention again. What has put them back on the agenda is the involvement of universities, which are starting to offer ISAs through their financial-aid offices, with outside investors providing some of the capital. Universities spy a way to lower their students’ debt burden and spare them from having to take out private loans. Investors regard this as a sign that an institution is confident in its graduates’ earning power, which reassures them about the extra risk in an equity arrangement, compared with conventional student debt.

Purdue introduced ISAs in 2016. The first participants graduated last year, having used ISAs to cover fees of $12,000 on average. Funding came from its endowment, which saw returns of 5-7%. Now it is raising capital from outside investors. Two other universities, Clarkson University in New York and Lackawanna College in Pennsylvania, have recently begun ISA schemes. One investor expects that another dozen will follow this autumn. The share of income signed over ranges from 2% to 17%, with students in high-earning fields, such as medicine or engineering, usually paying a smaller share of earnings for a shorter time than students of literature or fine art.

For investors, the safest bets are students on vocational courses—nurses, plumbers, computer programmers and the like—where postgraduate employment is the express aim and wages are predictable. The difficulty with less vocational subjects is in assessing whether a course will boost salaries sufficiently for the deal to make sense. Most universities rely on alumni surveys to find out how much their graduates earn, so data are patchy.

The stock of ISAs is tiny. Some 3,000-5,000 American students have used them to cover $40m in tuition costs, estimates Charles Trafton of FlowPoint Education Management, which creates and invests in ISAs. For comparison, in the 2016-17 academic year, private student loans totalled $11.6bn. Mr Trafton says he is buying ISAs for their combination of social impact and an investment return that he believes will match or exceed those for private loans, which are in the range of 4-15%.

Only universities that are confident of their courses’ value on the jobs market will be interested in partnering with investors, says Mr Trafton. “Those that know their tuition is overpriced and unconnected to the economic value of their degrees will never have ISAs.” He puts the latter cohort at 70% of four-year universities.

Universities that do take the plunge will be tracking their graduates closely. That in turn will make pricing easier and help expand the market. Over time they will get fine-grained data on their graduates’ employment and salaries, says Tonio DeSorrento of Vemo Education, which operates ISAs for several institutions. Some may even adjust their educational offerings to protect their investments.